The Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA4) is the first U.S. National Climate Assessment (NCA) to include a chapter that addresses the impacts of climate change beyond the borders of the United States. This chapter was included in NCA4 in response to comments received during public review of the Third National Climate Assessment (NCA3) that proposed that future NCAs include an analysis of international impacts of climate change as they relate to U.S. interests.

This chapter focuses on the implications of international impacts of climate change on U.S. interests. It does not address or summarize all international impacts of climate change; that very broad topic is covered by Working Group II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC; e.g., IPCC 20141). The U.S. government supports and participates in the IPCC process. The more focused topic of how U.S. interests can be affected by climate impacts outside of the United States is not specifically addressed by the IPCC.

The topics in the chapter—economics and trade, international development and humanitarian assistance, national security, and transboundary resources—were selected because they illustrate ways in which U.S. interests can be affected by international climate impacts. These topics cut across the world, so the chapter does not focus on impacts in specific regions.

The transboundary section was added to address climate-related impacts across U.S. borders. While the regional chapters address local and regional transboundary impacts, they do not address impacts that exist in multiple regions or agreements between the United States and its neighbors that create mechanisms for addressing such impacts.

The science section is part of the chapter because of the importance of international scientific cooperation to our understanding of climate science. That topic is not treated as a separate section because it is not a risk-based issue and therefore not an appropriate candidate to have as a Key Message.

The U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP) put out a call for authors for the International chapter both inside and outside the Federal Government. The USGCRP asked for nominations of and by individuals with experience and knowledge on international climate change impacts and implications for the United States as well as experience in assessments such as the NCA.

All of the authors selected for the chapter have extensive experience in international climate change, and several had been authors on past NCAs. Section lead assignments were made based on the expertise of the individuals and, for those authors who are current federal employees, based on the expertise of the agencies. The author team of ten individuals is evenly divided between federal and non-federal personnel.

The coordinating lead author (CLA) and USGCRP organized two public outreach meetings. The first meeting was held at the Wilson Center in Washington, DC, on September 15, 2016, as part of the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Adaptation Community Meetings and solicited input on the outline of the chapter and asked for volunteers to become chapter authors or otherwise contribute to the chapter. A public review meeting regarding the International chapter was held on April 6, 2017, at Chemonics in Washington, DC, also as part of USAID’s Adaptation Community Meetings series. The USGCRP and chapter authors shared information about the progress to date of the International chapter and sought input from stakeholders to help inform further development of the chapter, as well as to raise general awareness of the process and timeline for NCA4.

The chapter was revised in response to comments from the public and from the National Academy of Sciences. The comments were reviewed and discussed by the entire author team and the review editor, Dr. Diana Liverman of the University of Arizona. Individual authors drafted responses to comments on their sections, while the CLA and the chapter lead (CL) drafted responses to comments that pertained to the entire chapter. All comments were reviewed by the CLA and CL. The review editor reviewed responses to comments and revisions to the chapter to ensure that all comments had been considered by the authors.

Key Message 1: Economics and Trade

The impacts of climate change, variability, and extreme events outside the United States are affecting and are virtually certain to increasingly affect U.S. trade and economy, including import and export prices and businesses with overseas operations and supply chains (very likely, medium confidence).

Description of evidence base

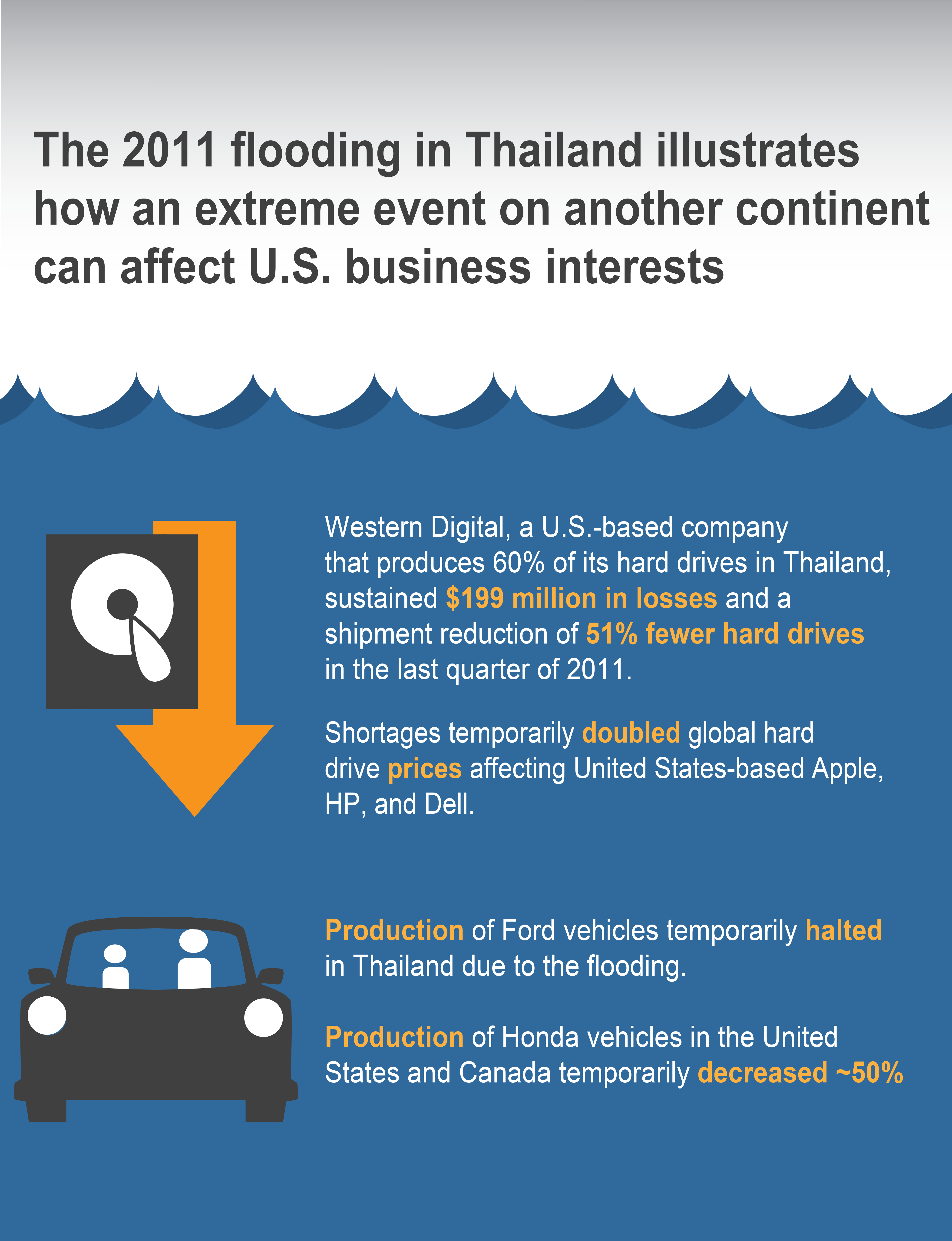

Major U.S. firms are concerned about potential climate change impacts to their business (e.g., Peace et al. 2013, Peace and Maher 201510,11 and illustrative examples of SEC filings describing climate risks to U.S. companies operating abroad6,7,8,9). Examples include the 2011 food price spike20,21 and the 2011 Bangkok flooding; corresponding prolonged and cascading impacts to transportation and supply chains are documented in the citations related to those issues.23,24,25 Future changes in precipitation, temperature, and sea level (among other factors) are very likely, as described in USGCRP,3 and are very likely to exacerbate impacts on the U.S. economy and trade, relative to past impacts.

Major uncertainties

The literature base on the impacts of climate change outside U.S. borders to the U.S. economy and trade is significantly smaller than that on climate change impacts within U.S. borders. In particular, few studies have attempted to quantify the magnitude of the past impacts of climate variability and change that occur outside the United States on U.S. economics and trade. Since there is limited literature, it is unclear how climate-driven regional shifts in economic activity will affect U.S. economics and trade. Nonetheless, the general nature of the main types of impacts described in this section are relatively well known.

Description of confidence and likelihood

The portion of the main message pertaining to the future is very likely due to the likelihood of future climate change3 and persistence of the sensitivity of the U.S. economy and its trade to climate conditions. There is medium confidence that climate change and extremes outside the United States are impacting and will increasingly impact our trade and economy because there is insufficient empirical analysis on the causal relationships between past international climate variations outside the United States and U.S. economics and trade to provide higher confidence at this time. No attempt was made in this chapter to define the net impact of international climate change on the U.S. economy and trade; such a statement would have had very low confidence due to the current paucity of quantitative analyses.

Key Message 2: International Development and Humanitarian Assistance

The impacts of climate change, variability, and extreme events can slow or reverse social and economic progress in developing countries, thus undermining international aid and investments made by the United States and increasing the need for humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (likely, high confidence). The United States provides technical and financial support to help developing countries better anticipate and address the impacts of climate change, variability, and extreme events.

Description of evidence base

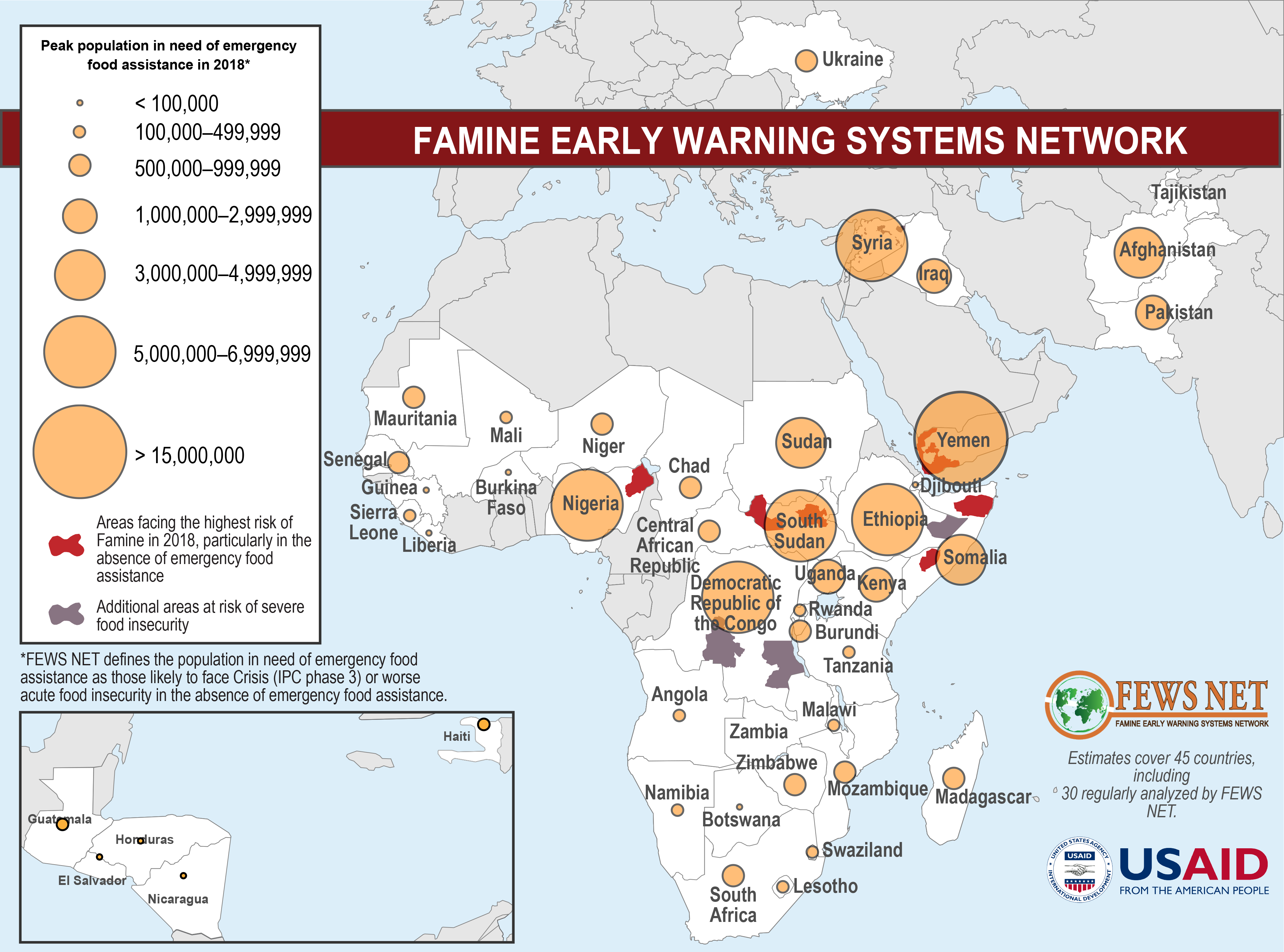

The link between climate variability, natural disasters, and socioeconomic development is fairly well established (e.g., UNISDR 2015, Hallegatte et al. 2017149,150), though some uncertainties about this relationship remain.151 Humanitarian disasters driven by climate impacts have led to specific changes in U.S. development assistance. For instance, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) was created after the droughts that contributed to mass starvation in Ethiopia in the mid-1980s. More recent crises in the Horn of Africa prompted major investments in resilience at the USAID.152

The relationship between climate change and socioeconomic development has been assessed extensively by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change through its assessment reports (e.g., IPCC 20141). There is some research on the economic costs and benefits from climate change (e.g., Nordhaus 1994, Stern et al. 2006, Estrada et al. 2017, Tol 2018153,154,155,156). However, it can be difficult to separate climate impacts on a sector from the role of other impacts, such as weak governance (Ch. 17: Complex Systems).

The United States has long invested in socioeconomic development in poorer countries with the intention of reducing poverty and encouraging stability. Additionally, stable and prosperous countries make for potential trading partners and a reduced risk of conflict. These ideas are presented in numerous U.S. development, diplomacy, and security strategies (e.g., U.S. Department of State and USAID 2018, 201540,41). There is ample evidence that the United States has invested in measures to reduce climate risks and build resilience in developing countries (e.g., USAID 2016157). However, this chapter does not assess the efficacy of these efforts.

Major uncertainties

Climate change adaptation is an emerging field, and most adaptation work is being carried out by governments, local communities, and development practitioners through support from development agencies and multilateral institutions. Evaluations of the effectiveness of adaptation interventions are generally conducted at the project level for its funder, and results may not be publicized. Some research is emerging on the economic benefits of adaptation interventions (e.g., Hallegatte et al. 2016, Chambwera et al. 2014158,159). Over time, it is likely that more activities will be implemented, more evaluations will be conducted, and the evidence base will grow.

Description of confidence and likelihood

There is high confidence in the Key Message. There is ample evidence that the impacts of climate variability and change negatively affect the economies and societies of developing countries and set back development efforts. There is also evidence of these impacts leading to additional U.S. interventions, whether through humanitarian or other means, in some places.

Key Message 3: Climate and National Security

Climate change, variability, and extreme events, in conjunction with other factors, can exacerbate conflict, which has implications for U.S. national security (medium confidence). Climate impacts already affect U.S. military infrastructure, and the U.S. military is incorporating climate risks in its planning (high confidence).

Description of evidence base

Based on an assessment of a wide range of scientific literature on climate and security, multiple national security reports have framed climate change as a stressor on national security.59,60,62,160,161,162,163 A large body of research has examined how stress due to adverse climatic conditions may affect human and national security in relation to conflict. While a few studies clearly link climatic stress to insecurity conflict,164,165 more often studies do not find a measurable direct response.70,77,82,166,167,168,169,170 Instead, the relationship between climate and conflict is often framed as climate stress affecting conflict through intermediate processes, including commodity price shocks and food and water security, which are themselves documented stressors on conflict.61,71,72 Many studies focus on Africa, but evidence exists throughout the world.76,77,78,80,81,82,83 Additional complexity arises from evidence of a range of societal responses to resource scarcity such as that brought on by climate change and natural variability.61

The U.S. military is observing climate change impacts to its infrastructure and is taking a scenario-driven, risk-based approach to address resultant challenges. Exceedance probability plots of the type used to support engineering siting and design analysis were used but modified to include responses to time-specific tidal phases and historical trends to create an estimate of the “present day” exceedance probability. The hindcast projections kept pace with an Intermediate-Low sea level rise scenario of approximately 5 mm/year (about 0.2 inches/year).171 The focus for Department of Defense (DoD) infrastructure management, however, is the resultant increased trend for exceedances that would challenge infrastructure functional integrity (such as negative impacts to critical roadways and airfields).171 In an effort to understand risks to the integrity of coastal facilities more broadly, the DoD uses a scenario-driven risk management approach to support decision-making regarding its coastal installations and facilities. The scenario approaches provide a framework for the inherent uncertainties of future events while providing decision support. Scenarios are not simply predictions about the future but rather plausible futures bounded by observations and the constraints of physics. Using scenarios, decision-makers can then examine risks through the lens of event impacts, costs of additional analysis, and the results of inaction. In this way, inaction is recognized as an important decision in its own right.64

Major uncertainties

The impact and risk of conflict related to climate change is difficult to separate from other drivers of environmental vulnerability, including economic activity, education, health, and food security.61,70 There is currently a lack of robust theories that fully explain causality and associations between climate change and conflict.

Datasets on climate change, conflict, and security are often limited in length and pose statistical difficulties.70 However, recent advances in statistical analysis have begun to allow the quantification of indirect effects of multiple variables connecting climatic pressures and violence.172 These results are preliminary, mostly due to a lack of necessary data and the difficulty of quantifying relevant social variables, such as identity politics or grievances. There is a widespread pattern of examining instances of conflict for drivers, precluding the possibility of finding that climate-related stressors did not result in conflict. There is a need to analyze situations where no conflict occurred despite existing climate risks. Intercomparison of quantitative studies of the link between conflict and adverse climate conditions is complicated because the wide range of climatic and social indicators differ in spatial and temporal coverage, often due to a lack of data availability. Prehistoric and premodern evidence of the impact of climate change on conflict is not necessarily relevant to modern societies,167 and some of the climate shifts currently being faced are unprecedented over centuries to millennia.170 Therefore, the possible existence of a relationship is better understood than its particulars and is best expressed in the formulation that climate extremes and change can exacerbate conflict.

The ongoing Syrian conflict is often framed in terms of climate change. However, it is not possible to draw conclusions on the role of climate in the outcome of an ongoing conflict. Moreover, the role of climate variability (such as drought), the contribution of climate change to such variability, and the contribution of climate variability to the subsequent conflict is a matter of active debate in the assessed literature.173,174,175,176

The documented impacts of climate on national security largely occur through processes associated with natural climate variability, such as drought, El Niño, and tropical storms. While observed and projected increases in extreme weather and climate events have been attributed to climate change, uncertainty remains.48,177,178,179

Similarly, additional studies are underway to determine the potential impacts of climate change on DoD resources and mission capabilities. Many of these efforts seek to assess the vulnerability of infrastructure to climate change across a wide variety of ecosystems.180,181,182

Description of confidence and likelihood

There is consensus on framing climate as a stressor on other factors contributing to national security. Given the knowledge of factors that increase the risk of civil wars, and evidence that some of these factors are sensitive to climate change, the IPCC found justifiable concern that “climate change or changes in climate variability [could] increase the risk of armed conflict in certain circumstances.”61 However, the literature examining specific causality does not result in a high confidence conclusion to link climate and conflict, which is reflected in the Key Message medium confidence assignment. Multiple schools of thought exist on the mechanisms and degree of linkages, and models are incomplete. Data are improving and evidence continues to emerge, but the inconsistent evidence limits our ability to assign a probability to this Key Message.

Nonetheless, with regard to climate impacts on physical infrastructure, the DoD observes changes in the infrastructure at its installations that are consistent with climate change. In keeping with sound stewardship and prudence, it uses scenario-driven approaches to identify areas of risk while continuing to research and provide resilient responses to the observed changes.

Key Message 4: Transboundary Resources

Shared resources along U.S. land and maritime borders provide direct benefits to Americans and are vulnerable to impacts from a changing climate, variability, and extremes (very likely, high confidence). Multinational frameworks that manage shared resources are increasingly incorporating climate risk in their transboundary decision-making processes.

Description of evidence base

In the U.S.–Mexico drylands region, large areas are projected to become drier,102 which will present increasing demands for water resources on top of existing stresses related to population growth.103,104 There is high confidence that resources critical to livelihoods at borders between the United States and neighboring nations are becoming increasingly vulnerable to impacts of climate change and that the multinational frameworks that manage these resources are increasingly incorporating research-based understanding of the climate risks that these resources face. The literature supporting the Key Message is substantial, increasing in quantity and robustness.96,97,98,99,100,105 The current impacts are well documented, and the projections of future impacts are aligned with the robust projections of future climate variability.94,95 The literature also provides examples of bilateral agreements and management frameworks in place to manage these resources. Examples of the impacts include the migration northward into Canadian waters of Pacific hake, a migratory species sensitive to water temperature, during periods of warmer water temperature.100 One example of a bilateral management framework is the inclusion in 2012 of a climate change impacts annex to the U.S.–Canada Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement to identify, quantify, understand, and predict climate change impacts on the water quality of the Great Lakes.109

Major uncertainties

Impacts on shared resources along U.S. international borders are already being experienced. Uncertainties about the impacts are aligned with the uncertainties associated with projections of future climate variability. As elaborated upon in multiple regional chapters of this report (Ch. 18: Northeast; Ch. 20: U.S. Caribbean; Ch. 21: Midwest; Ch. 24: Northwest; Ch. 25: Southwest; Ch. 26: Alaska; Ch. 27: Hawai‘i & Pacific Islands), weather patterns in these border regions are projected to continue to change with varying degrees of likelihood and confidence.

Description of confidence and likelihood

There is high confidence in the main message. There is sufficient empirical analysis on the relationships between past climate variations along U.S. international borders. The statement about the likelihood that impacts on shared resources will affect the bilateral frameworks established to manage these resources is based on expert understanding of the integration of climate risk into existing and future frameworks.